If you missed parts one or two of this retrospective on Brazilian icon Garrincha, please follow the links.

Now for part three - on the dark side of irreverence.

He was never interested in money; he was simple and, for him, football was fun.

Elza Soares

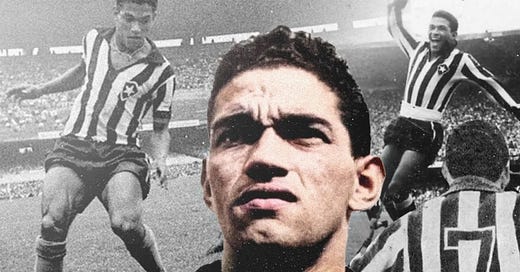

Sandro Moreyra, despite his noble pledge, was unable to really protect Garrincha from the cut-throat world of football. At Botafogo his status at the club veered from untouchable idol to money-grabbing mercenary, despite his contracts being put in front of him without any figures on them, and despite the ton of money they made post-World Cups from lucrative European tours.

In fact, the first Botafogo contract he signed actually aware how much he was going to be paid was in 1962. But even then, despite a deal which promised him 150,000 cruizeros a month - double the amount he’d been earning since 1959 - and a signing on bonus worth around $10,000, he proceeded to leave it with the club’s treasurer. It was only when a friend, appalled he could be so careless with 3 million cruizeros, prompted him to act that he sought to track it down.

By then it was all gone; depreciated through inflation and the club’s deceitful decision to use it to pay salaries. They had to ask for a bank loan to give him any back. In all his time at Botafogo, Garrincha was consistently paid below the top earners in Brazilian football.

He was just too easy to take advantage of. The same unpredictability, nonchalance and wonderful irreverence which fuelled his showmanship on the field of play and wowed audiences, bled into areas of his life that caused him, and the many people who depended on him, nothing but trouble.

His fiscal blunderings were so notorious in Brazilian football that all players post-Garrincha often used the line ‘you are not treating me like Garrincha’ as a means of ensuring they got a fair contract.

The problem was not always just that he was being underpaid by his club - despite the year 1961 marking an era of unprecedented success and social caché for Botafogo, in which they went 22 games unbeaten with a forward line to rival that of any club in any era: Garrincha, Didi, Amoroso, Amarildo, and Zagalo - but that his rapidly advancing alcoholism and continual self-indulgence meant he frittered away any money he had.

Or, with perhaps good intentions but really, appalling negligence, would put it for safe-keeping somewhere and completely forget about it. Journalist friend Ze Luis was staggered to learn one day that Mane had given a load of money to his wife Nair, which was then put in a dirty mattress and left. By the time anyone thought to recover it years later, the money was as decayed as his decor.

Salaries became a big issue at Botafogo during the second half of 1962. Even though the team was struggling to reach the levels of the previous years, the board were raking it in from lucrative exhibition matches. Amarildo negotiated a pay packet that was the highest at the club, Nilton Santos and Zagalo also received wage hikes but Garrincha was left stranded when he demanded the same 10 million cruizeros signing-on bonus Amarildo received. Talks hit an impasse before he was fobbed off with a one-bedroom flat in the Copacabana, which he reluctantly accepted.

The reckless abandon with which he approached his finances would perhaps not have been so terrible had Garrincha not, through a similar approach to women and sex, fathered 14 children (that he knew of) and had many mouths depending on his wages.

He’d married childhood sweetheart Nair in Pau Grande in 1952, where she remained with her phalanx of children in near-squalor, forced to accept the existence of other girlfriends and countless mistresses. Long-term beau Iraci was set up near him at Botafogo, but all of them quickly receded into the periphery once he’d fallen in love with singer Elza Soares in 1962.

Soarez was a famous TV star in Brazil, known for her sultry tones and samba, jazz fusion, and their emblematic relationship, full of amor fou and zest (they spent most of their time engaging in marathon sex sessions) but ultimately unstable, caused Garrincha much grief with his club. Not that it was Elza’s fault.

In 1963 Garrincha, fed up that he had not been paid the ten million bonus he had been promised, and desperate to renegotiate the final two years of his three-year deal, went to see the new Club Director of Football, Renato Estalita, who promised him that it would be resolved when they got back from their tour of South America, later that year.

Garrincha was concerned. He was having major problems with his knee which, because of the shape of his legs, had completely worn away the meniscus preventing his femur and tibia from rubbing together. His arthrosis was advanced. Not just because of the shape of his legs, but the explosive way he changed direction when playing.

Yet despite the agony it put him under, he repeatedly refused to do anything about it. He was so desperate to demonstrate to Estalita that he was worthy of a new deal that he frequently played despite the pain.

He needn’t have bothered. The club refused to bow to his demands, and his response quickly morphed into ‘pay me, or sell me.’ They didn’t want to do either.

Garrincha refused to kick a ball for them until it was resolved and, after three weeks passed in which Botafogo were losing but refusing to make amends, with Elza at his side, marched into the office for Radio Maua and went public on his fight with the club.

Botafogo were furious and, according to Castro:

An internal memo, signed by the club’s press director, called him a ‘scoundrel’ who ‘was taking advantage of Botafogo.’ Even Garrincha's teammates were irritated. The affair with Elza already bothered them, not because of Nair, who was not a popular figure, but because Garrincha had spent less and less time at the club since Elza’s arrival on the scene. He had played fewer games which, in turn, meant the others received fewer win bonuses.

Worse was to come. Reporters from O Globo tracked down Nair in Pau Grande and the full extent of Garrincha's infidelity was exposed. A whirlwind of press-fuelled sanctimony and public hatred engulfed the two of them and, though he eventually reached a truce with the club, things went from bad to worse in his personal life.

His love of cachaça was beginning to take its toll – not just on the man himself, but on those closet to him. Elza was the first to - literally – feel the effects after she was involved in a car crash with him at the wheel, and consequently lost two teeth.

Just weeks later they were rushing a boy to hospital who had run out in front of their car. The press coverage was intense. But that wasn’t the worst of it. In 1968 when his career was over, he crashed into a lorry on a highway. Elza's mother was beside him and died instantly.

The incident was to have a profound affect on Garrincha's life, as he was fully confronted with the shocking impact of his irresponsibility.

He responded by drinking himself into an abyss.

His alcoholism and financial squandering had already led to the exacerbation of his ruinous knee. He was desperate to make money after being hit with a huge tax bill and, in order to make regular payments to Nair, whose lawyer - fuelled by the tide of public opinion - was bleeding him dry, often had to have it drained of synovial fluid to play, worsening the condition and leaving him speechless with pain.

He repeatedly refused to go under the knife and would go missing for days whenever someone thought they had got him to agree to it. Botafogo's fans were beginning to lose patience with the one-time golden boy who never seemed to be playing, yet always seemed to be moaning about his wages.

He eventually did have an operation in 1964, but behind Botafogo's back. Another cut in amongst the thousand between player and club that led to their eventual parting of ways. And by then the damage was done – Garrincha’s days of dribbling were all but over.

He was selected for the initial World Cup squad in 1966 but was nowhere near the player he had been; alcohol and injury had ravaged one of the game's true greats and he was duly cut from the final 23.

As things at Botafogo soured he moved to Corinthians for one last throw of the dice. Despite winning two Rio-São Paulo tournaments, three Carioca State Championship titles and scoring 232 goals at Botafogo, his career there ended with a whimper:

1965 marked the end of the great Borafogo side. His last appearance was on the opening day of the Carioca Championship against Portgueuesa on 15 September. It was a Wednesday night, and 5,309 people turned up at the General Severiano stadium. The crowd almost within touching distance of the players but Garrincha had never been further from the fans. There was no love, not even any hate, between them, just a mixture of pity and indifference.

Corinthians used him to generate revenue but, saturated with vast amounts of cachaça and various other liquor, and shorn of its explosive pace off the mark and change of direction, his body could no longer perform as he bid it.

Worse still, the mental spores of his vice had stealthily grown around his mind like creeper vines and were mercilessly throttling his personality. Even moves to Colombia and Italy with Elza - as they attempted to keep some kind of control over their wildly fluctuating fortunes - couldn't rejuvenate the one-time good-natured rogue.

The CBD quickly grew tired of his request for handouts, but they did finally bow to pressure from Elza and others in the game to hold a testimonial. Even though he earned a sizeable amount of money to pay of his debts, onlookers watched on with tragic resignation as he and his wife squandered it on an absurd idea to build a restaurant in Rio.

Not only did the careless indifference which so characterised his life lead to its collapse, but it put Garrincha in an environment where he had ready access to the one substance which was to rob him of his joy. Several times he attacked Elza as alcoholism devoured him and, eventually, showing the instinct for self-preservation that had defined her own life, she left him.

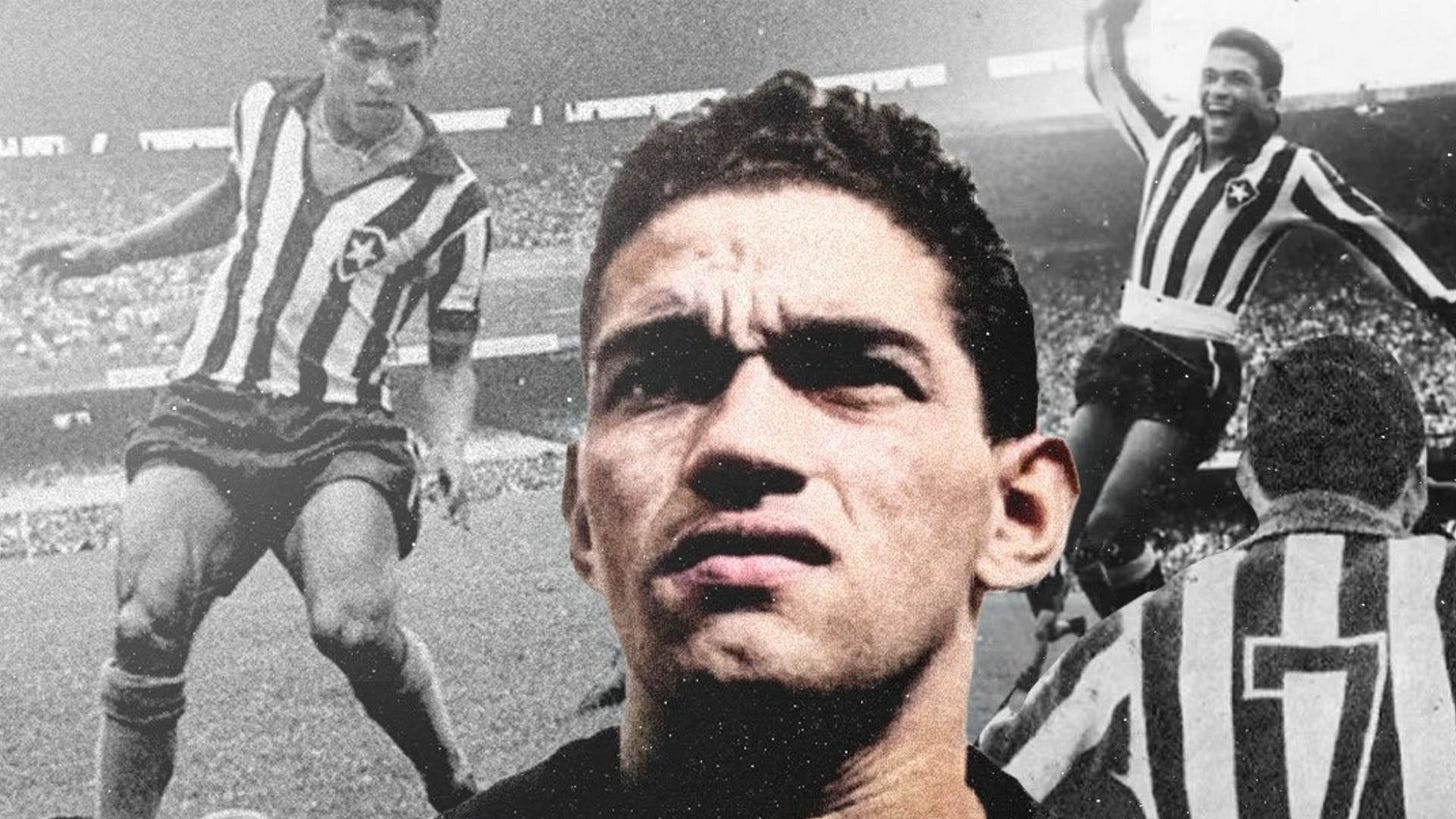

The carnival in Rio in 1980 provided some of his former teammates, and the watching world, with a tragic reminder of his disintegration. Grotesquely juxtaposed with the youth and vibrancy of a sunlit parade, Garrincha was seen semi-comatose, aged and desiccated atop one of the carnival floats, prompting Pele, after throwing his former teammate a garland that failed to stir his consciousness, to shake his head in horror.

By then the cirrhosis of the liver - which caused him hallucinations, delirium tremens and all manner of vicious side-effects - had taken hold of the virtuoso and he died a depressingly early death at the age of 49.

FINAL THOUGHTS /WHERE MYTH AND REALITY MINGLE

...he acknowledged that although he was aware that Sandro Moreyra’s stories had turned him into something of a retard in the eyes of the public, he didn’t really care. To be honest, the public’s portrayal of him as a naïve fool was quite convenient. Everyone loves a fool, which is often what gets them off the hook.

Ruy Castro.

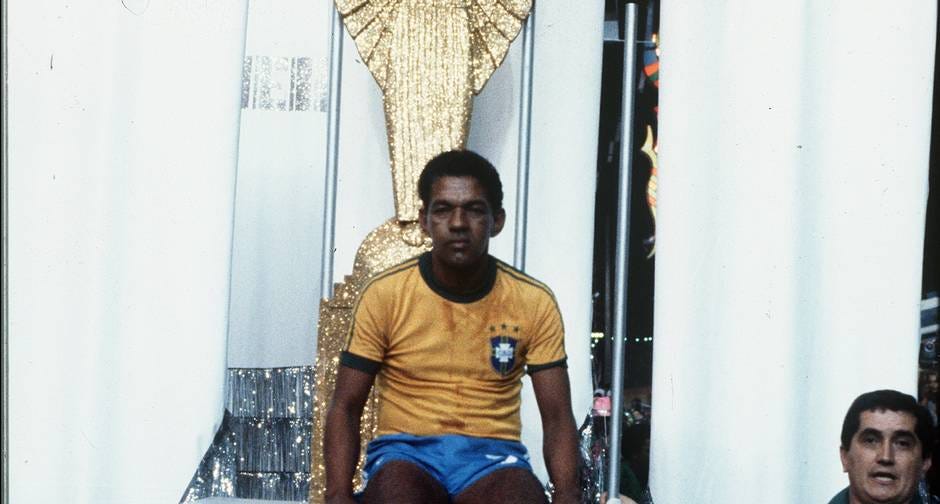

They say that your character is your destiny and that certainly holds true for Garrincha. One of the most problematic things about a retrospective on the Brazilian is that, despite a variety of superbly written accounts, not least by Castro, there is very little by way of words from the man himself.

He appears to have been as his nickname suggested - shy, reticent and largely indifferent to the passion he awoke in anyone who saw him on the field of play.

Whenever there is a vacuum of information, coupled with fervent interest in something, that space is always filled by words and thoughts that either reflect the desires and wishes of the interpreter(s), or else, are constructed from stories distorted and altered by the nature of their passage through culture and time.

Garrincha was often portrayed as a kind of idiot-savant; a Forest Gump-type figure who just put his head down and ran. But many of the stories - like the one about him thinking they had played each team twice in the 1958 World Cup, or that he called every player 'Joao' because to him they were non-entities he could beat on a whim, or that a delegation of players led by Nilton Santos was responsible for his inclusion in the 1958 World Cup match against Russia - were fabricated by people who were selling, or had bought into, an idea of Garrincha that was a caricature reimagining. But then, that is often the way of truth in the scaffolding of cult of personalities.

Ruy Castro provides an illuminating source for much of the Garrincha lore: Sandro Moreyra.

Moreyra invented the stories, tested them on Joao Saldanha and had a ball telling them to Mario Filho (an influential sports journalist) whom he didn’t like and whom he enjoyed getting the better of. Filho listened to the tales, marvelling at Garrincha’s simplicity, and then asked Moreyra’s permission to reproduce them in the book he was writing, The 1962 World Cup. He had been told that many of his stories were fiction, but Filho preferred to believe them. After all, Neither Moreyra nor Filho ever thought the stories would be distorted and twisted so that Garrincha would come to be seen unfairly as an infantile, almost pathetic genius.... Garrincha didn’t like the stories. He didn’t want to hear that he was invincible. He looked in the mirror, and saw a simple, ordinary man.

By all accounts, Garrincha was an uneducated person who indulged himself by doing only what he enjoyed, and the carefree wantonness that was the hallmark of his approach to everything, hinted at a simplicity of spirit. But as well as giving people a false impression, the stories did have another, more insidious effect - they too, gave him another means to escape responsibility.

His lack of an education meant he could hide behind a facade of childlike innocence, thereby escaping all manner of transgressions that were to have a cumulative negative effect on the boy from Pau Grande and those around him. His persona was a smokescreen; one that nurtured both the good and bad within.

Does the Little Wren deserve much sympathy? His attitude, whilst delighting football fans, destroyed many close to him and, whichever way you look at it, his life was defined by the manner in which he enjoyed himself. Like all of us really.

But then, the ability to entertain with such purity is an incredible power and, given the nature of modern consciousness and the era of hyper-accountability it has ushered in, its incredibly sad to think we are unlikely to ever again witness someone bewitch the watching world with such a unique combination of character and on-the-ball sorcery.

No club, coach or fan would tolerate a footballer turning up to work still drunk on cachaça, or rely on a player who fails to follow simple tactical instructions; someone who plays purely for the joy of dribbling.

As indulgence is punished, as football idolises the collective, as tactical systems require more and more discipline, the cost is that we are steadily robbed of these mavericks.

Beyond the dark side of Garrincha’s idiosyncrasies, one large benefit on the field was his imperviousness to pressure. Whether he was utterly unaware of the magnitude of the events he took part in, or how much it meant to people to see a successful Brazil team, or whether he was aware and cared only about doing what he did best, is irrelevant. As soon as he stepped onto the pitch he performed in a World Cup final and a friendly in exactly the same manner – with joyous indifference.

Was he selfish? Yes, but gloriously so.

Simplicity is beauty, and Garrincha's approach to the game speaks to the romantic buried deep within us all. His remains were shown in the Maracana stadium after a funeral procession from Pau Grande, with millions of fans paying their last respects.

His coffin was draped in a Botafogo flag before he was finally taken to his final resting place in his hometown, where there is a small memorial expressing Brazil's love for the two-time world champion. It reads:

He was a sweet child / He spoke with the birds.

My favourite story about the Pau Grande native is that the chants of 'Ole!' which sweep grounds during moments of footballing superiority were first heard in Argentina, when Botafogo played River Plate in 1958.

Almost from the kick-off, whenever Garrincha dribbled the ball past the Argentine [full-back Vairo] or stuck it through his legs, the supporters in the Estadio Universitario roared 'Ole!' as if they were at a bullfight. To them, the jinks and feints that sent Vairo one way and anther were worthy of Ordonez or Dominguin, the great Spanish matadors of the era. Time after time Garrincha teased Vairo, and when he 'forgot' the ball and sprinted away with Vairo running after him the thousands of voices chanting 'Ole!' changed to peals of laughter.

What a wonderful way to cherish and vitalise a spirit whose mortal coil has been thrown off.

Garrincha dribbled, he dazzled, he delighted, he re-imagined the game and he did it on the biggest stage of them all; with a smile on his face.

Joy of the People. Angel with Bent Legs. Perfectly imperfect.

Ole!

This article originally appeared in Issue Zero of The Green, then was later extended & updated for Issue Seven.

Primary sources are Ruy Castro’s Garrincha: The Triumph and Tragedy of Brazil’s Forgotten Football Hero & Alex Bellos’ Futebol: The Brazilian Way Of Life.